What do you think of when you hear the words “disability” and “Africa”? Perhaps an image of poverty-stricken children with polio comes to mind, or maybe you’ll picture charities like Doctors Without Borders working tirelessly to better the sickly.

While there is still a lot of work to be done in furthering disability rights and dismantling ableism throughout Africa, the continent is so vast, so full of history and so rich with culture that, for centuries, there has been plenty of time devoted to considering special needs. People with all kinds of disabilities have been the subject of folkloric tales, spiritual icons, sources of wisdom and symbols of togetherness and respect.

There is a more wholesome, holistic and spiritual view of disability in most traditional communities: there is less focus on “fixing” or “rehabilitating” various physical and mental limitations, but rather an acceptance of people’s different needs, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. While it is important to note that some tribes and societies are guilty of ableism (and modern societies are not much better), acceptance, inclusion and reverence of the differently-abled is quite common.

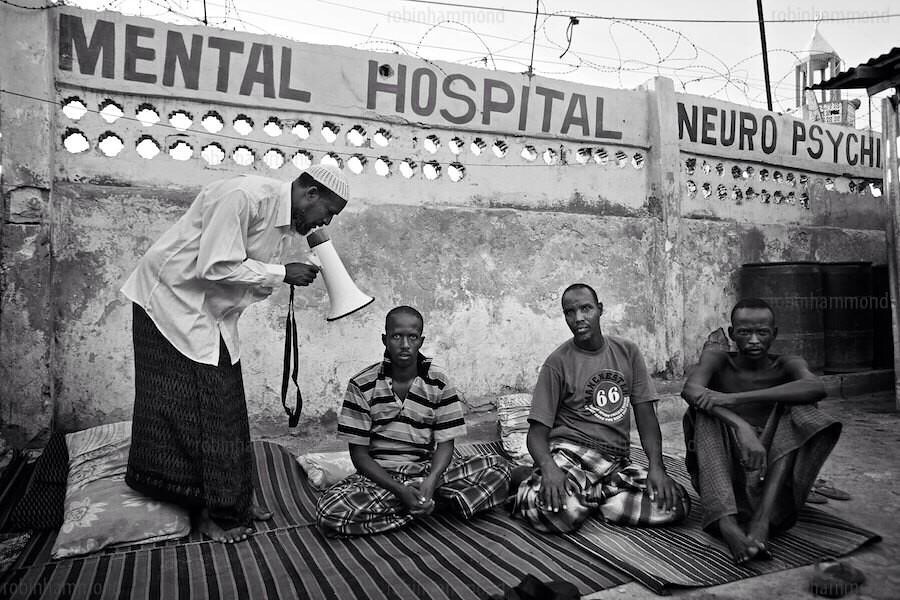

|

| Flickr | Robert Hammond |

In contrast to western concepts, disability is not usually seen as one conglomerate: for instance, in Tanzania, the term “ulemavu” has only recently been used for disability in general. Throughout history, different disabilities have been considered separately from one another: deafness and paraplegia would not be seen as related issues. Although, more similarly to western definitions, some indigenous societies define disability as “a limitation in social role functions resulting from physical, sensory or emotional abnormalities and is of a spiritual nature” (Interestingly, emotional issues have yet to be fully accepted by mainstream society as disabilities).

It’s widely considered rude to laugh at somebody’s disability. A Songye proverb says “Tosepanga lemene, Efile kiakupanga” — “Don’t laugh at the disabled person, God keeps on creating you”. It’s commonly thought that mocking disability would cause one to suffer disability, whether by a future accident or by bearing a disabled child.

Disability is also associated with great power. A person with one eye is said to see better than a two-eyed person. The Ga from the Accra region in Ghana believe that people with mental disabilities are reincarnations of deities, and are treated with kindness and patience. In Sub-Saharan Africa, any irregular birth — from breech birth to birth defects — is treated especially ritualistically. In Benin, children who were born with anomalies were believed to be protected by supernatural forces and brought good luck. The Kurkana of Kenya see such as children as gifts from God, and must be taken care of as well as possible, in fear of God’s wrath. In Tanzania, the Chagga people believed that people with disabilities protected the community from evil spirits by serving as a pacifier: the presence of a person with a disability satisfied the needs of the evil spirits, and in doing so was treated with respect for keeping the whole community safe.

It’s important to remember that, in many African countries, community is extremely important: family is seen as the most important social unit, not the individual. While this has been used against the differently-abled (in the sense that performing physical tasks to better the community is prized), this is also used as motivation to treat everybody with respect. A Shona proverb from Zimbabwe states “Benzi hunge riri rajo, kudzena kwaro unopurudza” — if someone with a mental disorder is a member of your family, you applaud his dancing.

The agency of a person with a disability isn’t taken away in many tribes. The Maasai of Kenya accept women with disabilities bearing children, and she is allowed to stay in her family home as “the girl of the homestead” instead of moving in with her husband’s family, which is a privilege in Maasai culture. In the same tribe, children with disabilities are treated the same as able-bodied children, participating in the same rituals. The Hausa people of northern Nigeria and southeastern Niger have disabled communities, represented by a leader with the same disability (this social structure goes for every community and profession in Hausaland).

Indeed, many African countries don’t see people with disabilities as being fundamentally different; a person with a specific impairment is seen as just that. The disability does not define who they are, and their contributions to their communities are valued as much as anybody else’s. According to many an East-African proverb, every person has been placed on the earth for a reason.

Sources:

http://www.rds.hawaii.edu/ojs/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/110/367

http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3197/3068

Encyclopedia of Disability - Volume 5

Hausa Superstitions and Customs